HOLY KEDLOCK by Bill Sweetman

If speed and range are your goals for an interceptor, you can’t beat the Lockheed YF-12. It’s hard to beat as a confusing story either. Technology demonstrator? Stalking horse for something quite different? Opportunistic effort to save a program in trouble? Possibly, all of the above.

North American’s F-108 Rapier Mach 3 interceptor was cancelled in September 1959. The F-108 was only eight months past mock-up review, following an on-again, off-again initial development. But the Rapier’s ASG-18 radar and GAR-9 missile combo, developed by Hughes, had started earlier than the F-108 itself and enjoyed more consistent support, and was not canceled along with the aircraft.

A few months later, in January 1960, the CIA awarded Lockheed a contract to build 12 A-12s. They would be purely photo birds, with a single pilot and one camera bay, and the goal was to operate them out of Area 51, thereby evading the British and German anoraks who had rumbled the U-2.

On May 1, 1960, Frank Powers’ U-2 was shot down near Sverdlovsk. No parades or hot hors d’oeuvres for him. Eisenhower approved a cover story that Khrushchev shot to smaller pieces than the airplane. The furious President banned any further overflights.

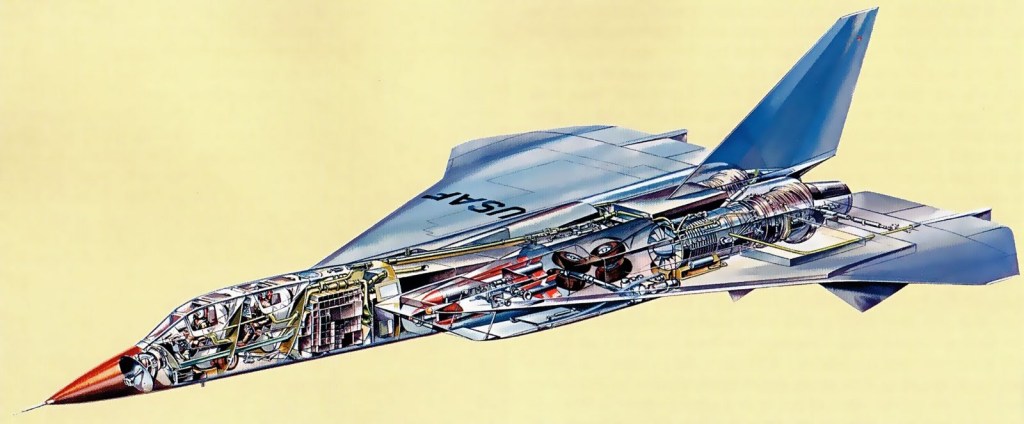

This left OXCART without a mission, barely six months into an expensive program, without a mission, and competing for money with the politically favored CORONA. Skunk Works boss Kelly Johnson proposed armed versions of the OXCART to the Air Force. It was risky because Air Force Chief of Staff Curtis LeMay was mounting a stalwart defense the XB-70 Valkyrie, but the interceptor version did not threaten the bomber. A contract was issued in October 1960 under which three A-12s would be completed as AF-12 interceptors with the F-108’s Hughes radar and missile system.

The AF-12, codenamed KEDLOCK, would feature some important differences from the CIA jets. Heavier and carrying more fuel, it would have a second cockpit replacing the camera bay, the massive ASG-18 radar in the nose, and four large weapon bays built into all-metal chines. (On the A-12, the chines were purely there to reduce the radar cross-section and were partly made of plastic material.) The GAR-9 was a 900-pound chonky boi and could carry either a high-explosive or blast-fragmentation warhead, with a range at launch up to 100 nm.

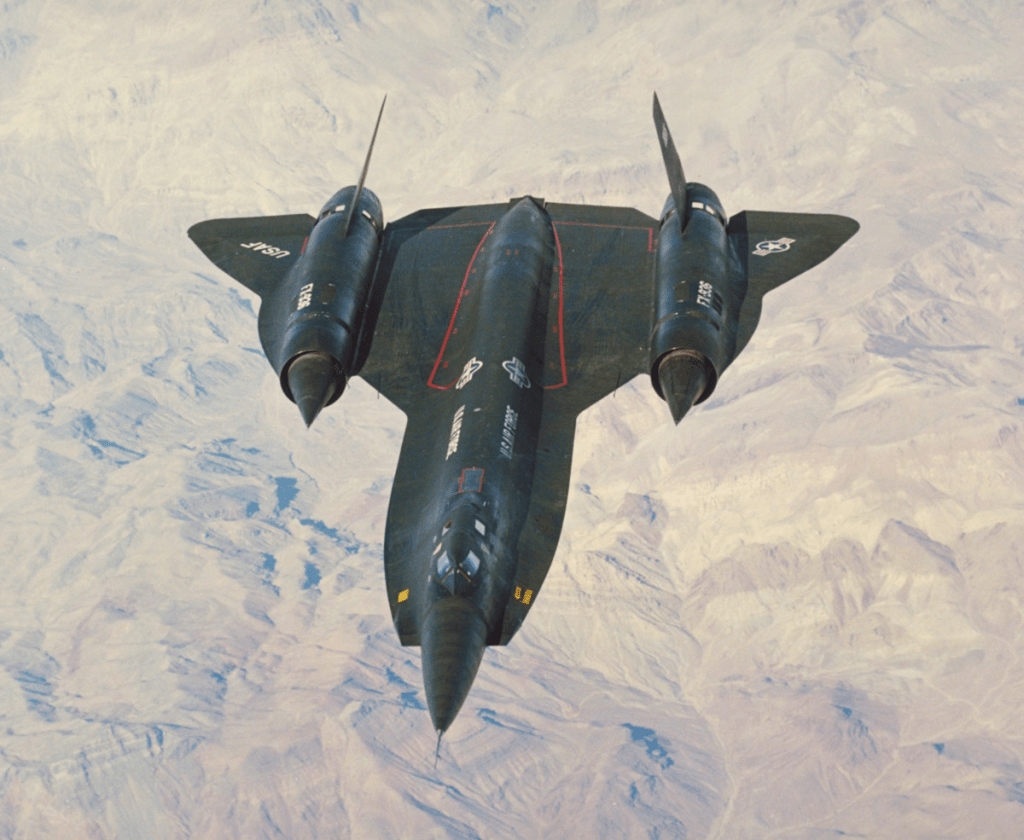

KEDLOCK benefited from the A-12 OXCART, which ran a year earlier and wrestled with the many basic problems of titanium use and propulsion development, and from the early start on ASG-18 and GAR-9. Wind tunnel tests showed that the huge ogival radome loused up the directional stability, so KEDLOCK acquired strakes under each engine nacelle and a large folding ventral fin.

Launching a weapon from a bay at Mach 3.2 was a challenge. Johnson’s deputy, Ben Rich, later said that the initial GAR-9 ejection system resulted in the missile passing between the front and rear cockpits, which would have been bad.

Flown in August 1963, the interceptor required little further work. Six out of seven missile shots were successful, the final shot from Mach 3.2 and 74,000 feet hitting a low-flying QB-47 drone—the first look-down, shoot-down interception and a trailblazer for the Navy’s AWG-9 and AIM-54 Phoenix programs.

KEDLOCK did a lot of the heavy lifting for the next version of the Blackbird, a reconnaissance-strike aircraft. First called RS-12, the project ran about a year behind KEDLOCK and emerged as the SR-71, with weapon bays converted to accommodate cameras and SIGINT gear.

The AF-12 had one more mission: deception. During 1963, as the pace of testing increased, observers started to notice the fast-moving A-12s and AF-12s, and the usual CIA/USAF tactic of confusing their reports with UFO sightings wore thin. Also, the project was far larger than the U-2 and involved more people and subcontractors, and many people in industry began to connect the dots. Bob Hotz’s staff at Aviation Week went to the Air Force with the news. Hotz would hold the story but not if anyone else got near it.

McNamara decided that the interceptor could be unveiled without compromising the A-12, and his view prevailed over the CIA’s caution. On February 24, 1964, two side-view photos were released of what was falsely described as the Lockheed A-11, and Johnson announced that a number of A-11s were being tested at Edwards Air Force Base. To keep the facts consistent with the President’s statement, two AF-12s were rushed from Area 51 to Edwards and quickly rolled into a hangar, where the heat from their airframes set the sprinklers off.

Had there been anything for it to shoot down, the YF-12 (as it was retrospectively designated, sometime before August 1964) might have been the ultimate interceptor. But the Soviet intercontinental strike force, even into the 1980s, amounted to a small and dwindling number of early Tu-95s, which Air Defense Command’s F-106s could cope with, and the YF-12s lived out their days as NASA test assets.

35% funding reached! The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 3Â here: