From great wheezing imperial dinosaurs, via the drearily sensible to pleasingly mad speedsters, a ragtag bag of utterly appealing British airliners failed to enter service. Here are 11 of them.

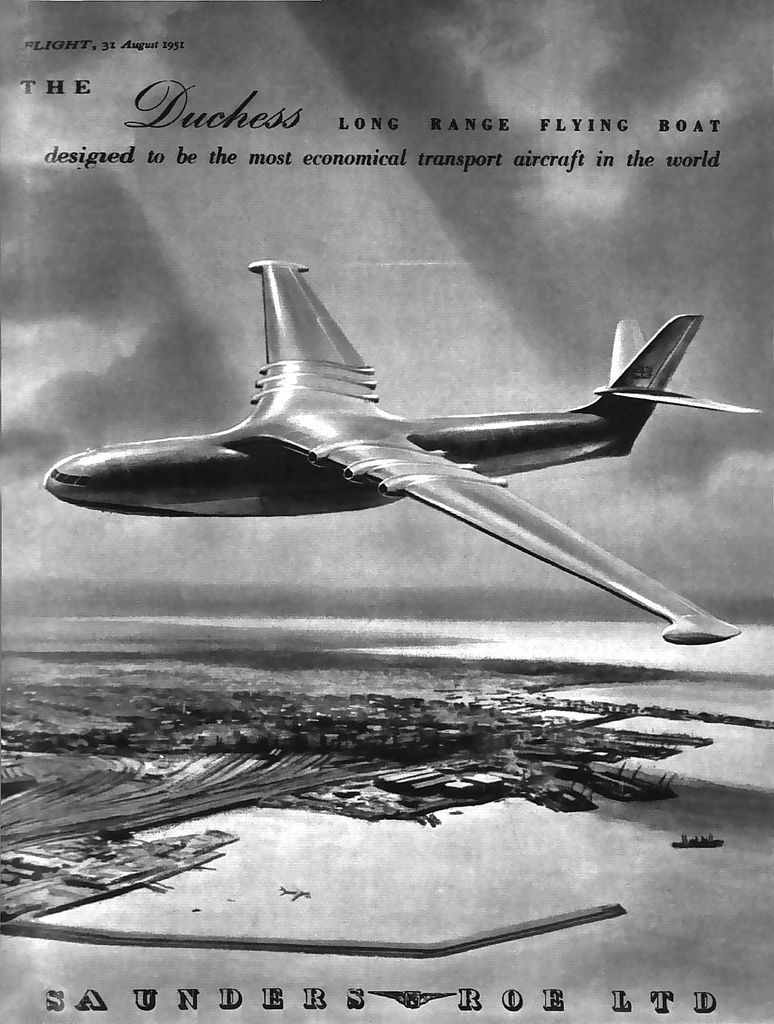

11. Saunders-Roe Duchess ‘Pass the duchy on the port-hand side’

The Isle of Wight in the English Channel was the last place in England to convert to Christianity. Against the menacing onslaught of Christian Anglo-Saxons, the isle’s 7th century King Arwald was defeated after a spirited fight. Despite his plucky attempts to resist the imposition of a new popular idea, he lost. In much the same way, Saunders-Roe Limited, a British aero- and marine-engineering company, also based on the Isle of Wight, failed to defend their strong belief that airliners (and fighters for that matter) should take off from water.

Each British aircraft manufacturer embraced the new jet engine in their own style: Gloster fitted it to an unadventurous airframe, de Havilland made a fast tiny jet fighter and a fast radical airliner, while SARO, stayed in the happy niche of flying boats (aeroplanes that land on the water on their hulls). The very large airliner SARO wished to build required a lot of power; one de Havilland Ghost jet engine can power a Vampire fighter – four a Comet airliner – but the impressively large Saunders-Roe Duchess would need six.

The extravagant Duchess was the ripped trouser crotch of a nation straddling the past and the future. While its performance and propulsion pointed to the future, its basic concept of operating from the sea (and its name) were paddling in the past. Inheriting much from the Princess (see below) the Duchess would have offered 74 passengers an exciting and glamorous experience on routes of up to 2,600 miles. If as if this wasn’t already wild enough, US companies Convair and Martin both designed and considered nuclear-powered Princess derivatives. However, the Duchess was (probably quite sensibly) cancelled.

Even the grand Duchess would have had to curtsy when the Queen appeared on the jetty.

10. Saunders-Roe Queen ‘Size Queen’

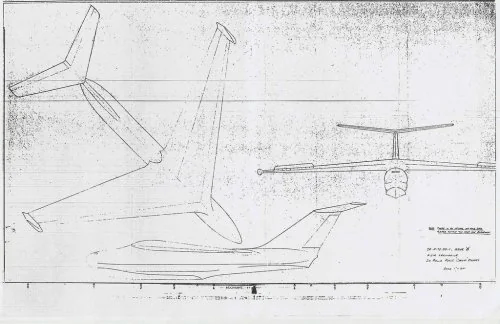

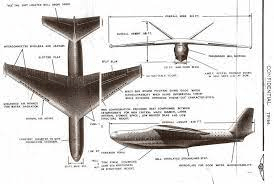

There must be something wrong with the thrust figure I’m about to tell you. In fact, please correct me so I can sleep again. The Queen was intended to have 24 Rolls-Royce Conway jet engines giving it a mind-bending total of 444,000Ib* of thrust. That cannot be right. That’s more than the most powerful aircraft ever flown, the An-225, with its relatively puny 309,600lb of thrust. I’m not a fan of exclamation marks, but they are utterly appropriate for the other mad facts about the proposed Queen. Such as the intended 1000 passengers carried in the luxurious comfort levels of an ocean liner(!) Or the 3000-mile range (!) or the 40,000 feet ceiling! This barnacle-encrusted behemoth was intended for intercontinental flights, especially for the Britain-Australia route.

The Princess was started after SARO was approached by one J. Dundas Heenan, consulting engineer from the firm Heenan in the 1940s. If that name is familiar to readers – this is because this is the rather bizarre Major J. N. D. Heenan behind the futiristically terrible Planet Satellite. Acting on behalf of the P & O shipping company Heenan was interested in a vast flying ocean liner. If this seems odd, then so does so much of Heenan’s life. I’d recommend clicking on the link on his name above where you can find out a bit more about this mysterious man.

SARO’s Queen was breathtaking in its ambition and vision, and quite possibly insane. Neither P&O nor the British Government could have hoped to have funded such a massive project, and the Queen quietly died.

* Figures vary for the Queen’s Conway’s quoted thrust but we have seen 18,500Ibs.

9. TRAMP! ‘Super Tramp’

The Gotha bombing raids of 1917 caused comparatively little material damage but a psychological response bordering on hysteria, not least due to these seemingly unstoppable attacks being launched in daylight. Knee jerk reactions included rioting in the East End of London, the changing of the British Royal Family’s surname from Saxe-Coburg Gotha to Windsor, and the Air Board issuing a requirement for an aircraft able to bomb Berlin. The Handley-Page V/1500 resulted from this requirement as well as the altogether more obscure Bristol Braemar and ultimately the Tramp, a vast steam-powered airliner.

As conceived by Bristol’s chief designer Frank Barnwell (unusual amongst aircraft designers in being a qualified military pilot and at this point riding high on the massive success of his superlative F.2b fighter) the Braemar was to be powered by four engines in an ‘engine room’ within the fuselage driving two propellers on the wings by means of clutches and shafts. However, a more conventional layout of two engines mounted back to back between each wing had (sensibly) been adopted by the start of 1918. Not quite as radical a feature but still an unusual choice was the use of the triplane layout, adopted to give a large wing area whilst avoiding an overly long wingspan. Completed in August, the Braemar was intended to be powered by four 360hp Rolls-Royce Eagle engines but shortage of these units saw 230hp Sunbeam Pumas substituted instead. Despite a shortfall of over a third in power, the Puma engined Braemar delivered surprisingly good performance, achieving a speed of 106mph but was prone to vibration and strut failures. A Mk II Braemar with four 400hp Liberty engines proved highly satisfactory and was remarkably fast. Despite the built-in headwind of three wings and the profusion of struts and bracing wires holding them together, it attained 125mph, slightly faster than the F.2b fighter and a full 23mph quicker than its direct competitor the V/1500. Unfortunately for Bristol, the new Braemar only flew during 1919 by which time any hope of a production order had evaporated with the end of the war.

But, already contracted to build three prototypes, it was suggested by the Air Board that the third aircraft be completed with a new fuselage as a 14 seat airliner. This duly emerged as the Bristol Pullman and caused a sensation when it was exhibited at the Olympia Airshow in 1920 due to both its huge size and luxurious passenger accommodation. Unusually for its era, the Pullman boasted luxurious accommodation for the pilots as well, in a fully enclosed and prodigiously glazed cockpit Рa feature predictably detested by the rugged pilots of the day as it compromised their view somewhat and they feared being trapped in the event of a crash. As a result, the Pullman test crew always brought axes aboard to hack their way out in the event of a mishap. Sadly, no airline orders were forthcoming but Barnwell had been in discussions with the Royal Mail Steam Packet shipping line about the possibility of using flying boats to transport passengers to and from ships at sea. With no experience of aircraft but a huge knowledge of steam turbine operations, the shipping company asked if Bristol could develop a 50 seat airliner powered by two closed cycle 1500hp Ljungstr̦m steam turbines. A Pullman development was proposed for the prototypes to develop the system to be followed by the definitive Tramp boats. Once again the power units were to be in the fuselage, driving propellers by shafts. Ultimately, the difficulties of creating a reliable high-pressure closed-loop steam system featuring boilers and condensers of a small enough size to fit in the aircraft proved insurmountable. Despite this, the two prototype Tramps were actually built but with four conventional Siddeley-Deasy Puma internal combustion engines in the engine room. All came to naught however as persistent problems with the clutch and gearbox system meant that flight was never attempted. This is a shame as had this aircraft proved successful, the enormous power and eerie smoothness of the steam turbine promised a level of speed, silence, and comfort in the mid-1920s unattainable by any aircraft until the advent of the turbojet.

8. BAC Three-Eleven ‘The Fat Troublemaker’

When I tweeted “Forget the bloody TSR-2, the BAC 3-111 was the biggest missed opportunity” there was a rather spicy reply from aviation journalist Bill Sweetman: “Bull (and I cannot emphasise too much) shite. I don’t know why this Three-Eleven mythology is emerging now. It was a BAC/RR spoiler after Airbus downsized the A300 (as in to 300 seats) to 250 and went with GE’s engines and HSA still doing the wing. With the rear engine weight penalty and RB.211-22, it would have far less growth potential than the A300B and certainly would have not developed into the A330/A340. Sure, Laker wanted it, but like the A300 it would have been too big for the charter biz.“

Depending on who you ask it was either the greatest lost opportunity of British aviation, or a wrong-headed deep-stall-cursed moneypit with the engines in the wrong place.

In the UK there were concerns that the Airbus A300 would not succeed, and a British wide-body with roots in the One-Eleven was seen as a viable alternative. It would however, have required large amounts of government money, and with British airliners’ unenviable reputation for profitability and a new Conservative Government unenthusiastic about state-sponsorship – this was a big ask. There were serious concerns about the design’s potential for deep-stall, and valid doubts that the rear-engine configuration was the right choice for a wide body. To make matters even worse for the 3-11, Britain was about to join the European Economic Community and the thought of creating a competitor to the A300, a flagship of European cooperation, was politically and diplomatically stinky. Maybe Bill Sweetman is right after all.

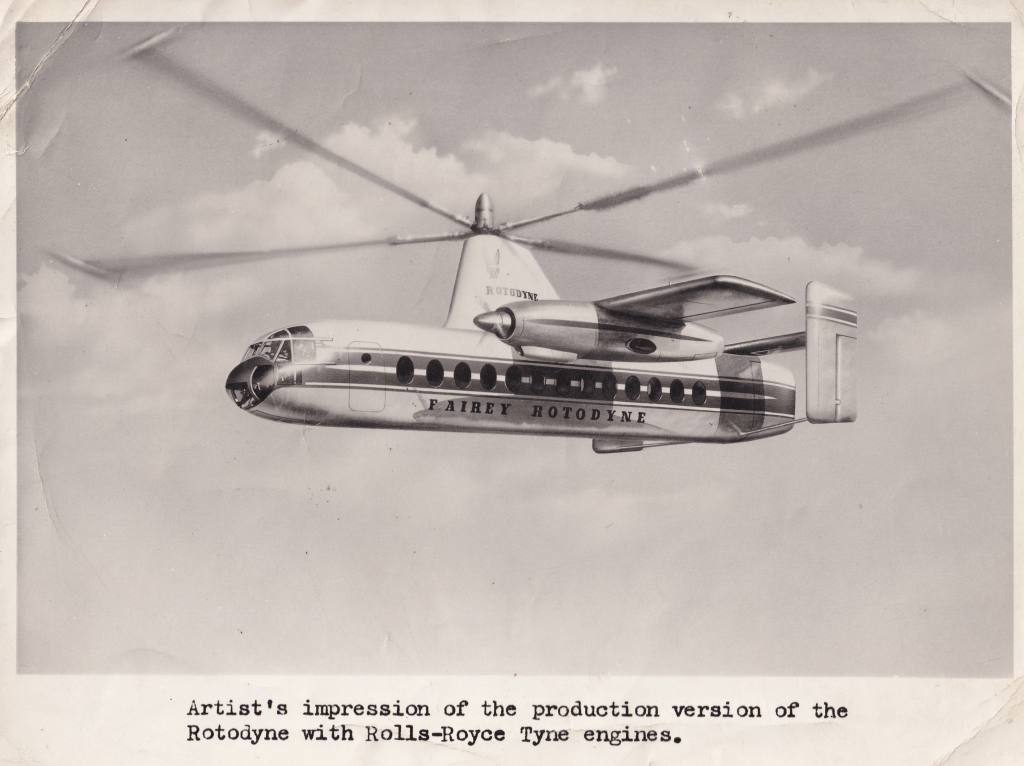

6. Fairey Rotodyne ‘The Screaming Megabus of the Sky’

In 1976 The Who seized the record for World’s Loudest Band from Deep Purple. Richie Blackmore’s group had enjoyed this prestigious accolade since 1972 when, at a gig in London’s Rainbow Theatre, three members of the audience were said to have been rendered unconscious by the volume. Measured at 126 dB 35m from a stage built at Charlton Athletic’s football ground, The Who’s new record stood for another eight years until broken by heavy metal band Manowar, after which the Guinness Book of Records abandoned the listing. Too likely to lead to hearing damage, they thought, depriving future generations of rock musicians this unholy race of eardrum destruction. Sadly, years earlier this kind of ‘namby pamby, ‘elf and safety gone mad‘ attitude also did for an innovative British airliner that had looked set to change the way the world flew.

‘The Fairey Rotodyne,’ said the narrator of a promotional film produced by the manufacturer, ‘is the aircraft for fast, economical travel offering the advantages of air transport to everyone, everywhere.’ Following the first flight in 1957, the future had looked bright. In flight-testing, the distinctive looking Rotodyne, resplendent in a smart blue and white livery, had set a world speed record and attracted the interest of airlines in Europe, North American and Japan. The RAF wanted a dozen and there were rumours that the US Army was up for as many as 200.

A unique hybrid, the Rotodyne cruised like an aeroplane, carried by stub wings and a freewheeling main rotor mounted on top of the fuselage, but could land and take off like a helicopter by bleeding air from the two turboprop engines through jets on the tips of the rotor blades. The merits of a fast, vertical take-off and landing, ‘flying bus’ capable of flying up to fifty passengers from city-centre to city centre were clear as Fairey’s advertising had claimed, but the failed to mention the noise. That, though, was what everyone else was talking about.

From over 150 metres away, the banshee scream of those four tip jets as loud as Baba O’Reilly from the mixing desk. Or a pneumatic drill from 15 metres. If the sound of breathing is 10 dB, the noise of a Rotodyne arrival was a whole lot closer to the 194 dB level at which a noise can get no louder without simply becoming a shockwave. To be fair, a Eurofighter Typhoon departing in full afterburner is louder than a Rotodyne. But only by the equivalent of the sound of rustling leaves. And Typhoons don’t routinely operate from in and out of densely populated city centres, but from airbases deliberately located far from them. The whole point of the Rotodyne was that it would.

Despite assurances from the project team that they could reduce it to acceptable levels, the siren scream of the Rotodyne became its defining characteristic. John Farley, the test pilot most closely associated with a British vertical take off success story, the Harrier, summed it up the general view: ”From two miles away it would stop a conversation. I mean, the noise of those little jets on the tips of the rotor was just indescribable. So what have we got? The noisiest hovering vehicle the world has yet come up with and you’re going to stick it in the middle of a city?“

Airline interest melted away and early in 1962 the government pulled the plug. By the end of the year the single prototype had been broken up for scrap. As the Rotodyne was unceremoniously torn up in Hampshire, in West London Pete Townsend, Roger Daltrey and John Entwistle played together for the first time.

Townsend now suffers from tinnitus and severe hearing loss. Similarly scarred by high volume, the UK’s aviation industry next attempt to build an airliner designed to fly in and out of urban airfields, prioritised reducing the noise footprint.

So successful were they in doing so that they attracted glowing headlines and promoted the little BAe 146 as the ‘Whisperjet’. Forty years on it remains in service with operators around the world, while all that remains of the spectacular, but unfortunate Rotodyne are a few sad bits and pieces in a museum in Weston-super-Mare.

- Rowland White, Author of this fabulous Mosquito book

5. MAYO! ‘Little & Large’

Potentially an exceptionally lucrative market, it was known that the Atlantic could be crossed by aeroplane since 1919 but remained tantalising just out of reach, in a practical sense at least, until the very last weeks of peace during 1939. The amount of fuel required to get an aircraft from London to New York (or vice versa) was simply so great that the aircraft could carry no passengers or cargo. To solve this seemingly insurmountable problem, Robert Mayo, Imperial Airways’ Technical General Manager proposed a system wherein a small, long-range seaplane on top of a larger carrier aircraft, used the combined power of both to bring the smaller aircraft to operational height, at which time the two aircraft would separate, the carrier aircraft returning to base while the other flew on to its destination. The upper component aircraft carried only mail so ultimately the description of the Mayo as an airliner is, frankly, pushing it a bit. Ah well.

The undeniably spectacular Mayo, consisted of a fairly heavily modified Short C-Class ‘Empire’ flying boat named ‘Maia’, and a totally new design, ‘Mercury’, the messenger of the Gods – though its not clear that the Romans had the delivery of air mail in mind for him originally. The connecting mechanism allowed for limited movement of both components relative to each other. When release was imminent, the flying trim of Mercury could be checked before the pilots released one lock each. The final lock holding the craft together was automatic, releasing Mercury when it achieved 3000 pounds-force (13 Kn). This meant that Mercury was effectively straining upwards and the effect was that on release Maia would tend to drop away whilst Mercury climbed sharply, minimising any chance of collision. The first separation was achieved in February 1938, followed by the first transatlantic flight on July 21st. After the Composite took off from Southampton, Mercury was released over Shannon in Ireland and continued alone to Boucherville, near Montreal in Canada, carrying half a ton of mail and newspapers. This represented the first commercial crossing of the Atlantic by a heavier-than-air aircraft. This was followed up by a record-breaking flight of 6,045 miles (9,728 km) from Dundee in Scotland to Alexander Bay in South Africa, between 6 and 8 October 1938. This remains the longest flight ever achieved by a seaplane. Ultimately aircraft development caught up with the Mayo composite. Although it achieved its design goal with considerable panache, it was an excessively complicated way to carry 1000 lbs of mail to America, not to mention colossally expensive. Economic calculations, hilariously carried out only after the construction of the Mayo composite showed that in order to turn even a minimal profit, it was necessary to prohibitively inflate postage costs. Thus, from the point of view of the Post Office the introduction of the Mayo made sense solely as a means to maintain the prestige of Great Britain as a credible aviation power: commercial success for the Mayo Composite was totally impossible.

- Ed Ward

4. Bristol Brabazon (1949) ‘The Village Slayer’

There was a lot going on in 1949, the Berlin Airlift ended, Churchill voiced his support for a European Union including Britain – and the results of a mass survey into the sexual behaviour of British people was deemed too spicy for publication. According to a BBC article on the survey, “One in four men admitted to having had sex with prostitutes, one in five women owned up to an extra-marital affair, while the same proportion of both sexes said they had had a homosexual experience.” When British people weren’t fucking they were designing lots of aeroplanes. Britain seemingly had more aircraft manufacturers than even extra-marital affairs.

Having recently studied a 100-ton bomber design in detail, in the mid 1940s the Bristol Aeroplane Company were in the best possible position to produce a massive transatlantic airliner. This was extremely ambitious for the time and Bristol would require the most powerful engines they could get their hands on, the seriously powerful Centaurus. Bristol had spent World War II making tough but relatively conservative or derivative designs, so this new venture was an extremely radical departure.

But technical problems, the high seat cost per mile from the luxurious low density configuration and the vast cost of the project all conspired to doom it to failure.

Plans to build a Mark II, with Proteus turboprops were scuppered by delays in the Proteus programme. The equivalent of £375 million was lost in the project – as was a village. But half of that figure paid for building work to the Filton plant that would aid many later aircraft projects.

Background

The history of post-war civil aircraft development in Britain is inextricably bound up with the deliberations of the Brabazon Committee. This was formed in December 1942, following a request from Winston Churchill, and was tasked with considering the development of civil air transport, in the context of British aircraft manufacture having been exclusively directed at the production of military aircraft. Any new aircraft would need to compete with American transport aircraft and their developments, with obvious examples including the Douglas DC-3, DC-4 and Lockheed Constellation, as well as subsequent US aircraft developments.

Although widely criticised, the Brabazon Committee proposed a series of specifications, from which successful and innovative aircraft designs were developed, funded through the UK Ministry of Supply. These included the ground-breaking de Havilland Comet and Vickers Viscount, the impressive Bristol Britannia, and the de Havilland Dove. Less successful designs included the Airspeed Ambassador and Miles Marathon, while the Bristol Brabazon, Armstrong-Whitworth Apollo, and (tangentially) the Saunders-Roe Princess can only be considered as failures.

3. Saunders-Roe Princess ‘The Salty Princess’

BOAC considered (in 1945) that there was still a market for long-range and luxurious flying boats, and the Princess was proposed by Saunders-Roe, and succeeded in attracting funding from the Ministry of Supply to meet a requirement to transport 100 passengers from London to New York, and on broader routes around the Empire to destinations that did not have large airports.

One aircraft only was flown, the largest all-metal flying boat ever to have been constructed. Powered by no less than 10 Proteus turboprops, with a ’double-bubble’ pressurised fuselage, it made only 46 flights, commencing in August 1952. Sadly, by this time, BOAC had ceased flying boat operations, having observed the widespread availability of airfields worldwide capable of operating the de Havilland Comet. As a result, the Princess project, which BOAC had itself initiated, was cancelled.

With no market for large civil flying boats, the three aircraft built were cocooned, and slowly corroded away until being scrapped in 1967. A fabulously impressive-looking aircraft, but a martyr to a failure to realise that the world had changed since the days of the Empire flying boat.

– Jim Smith

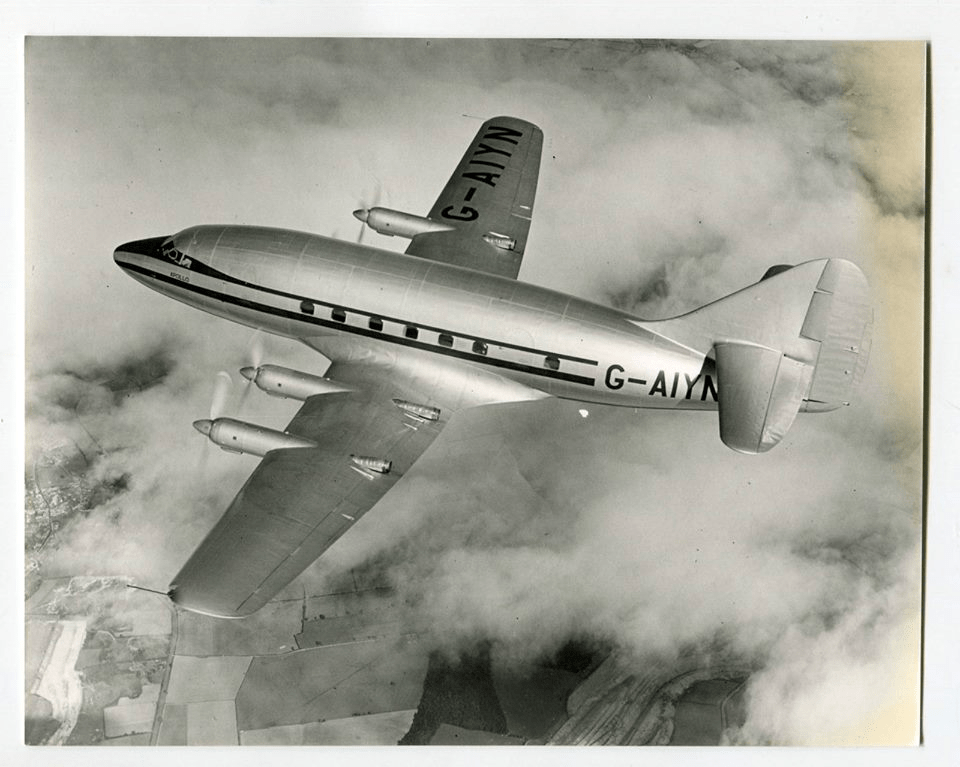

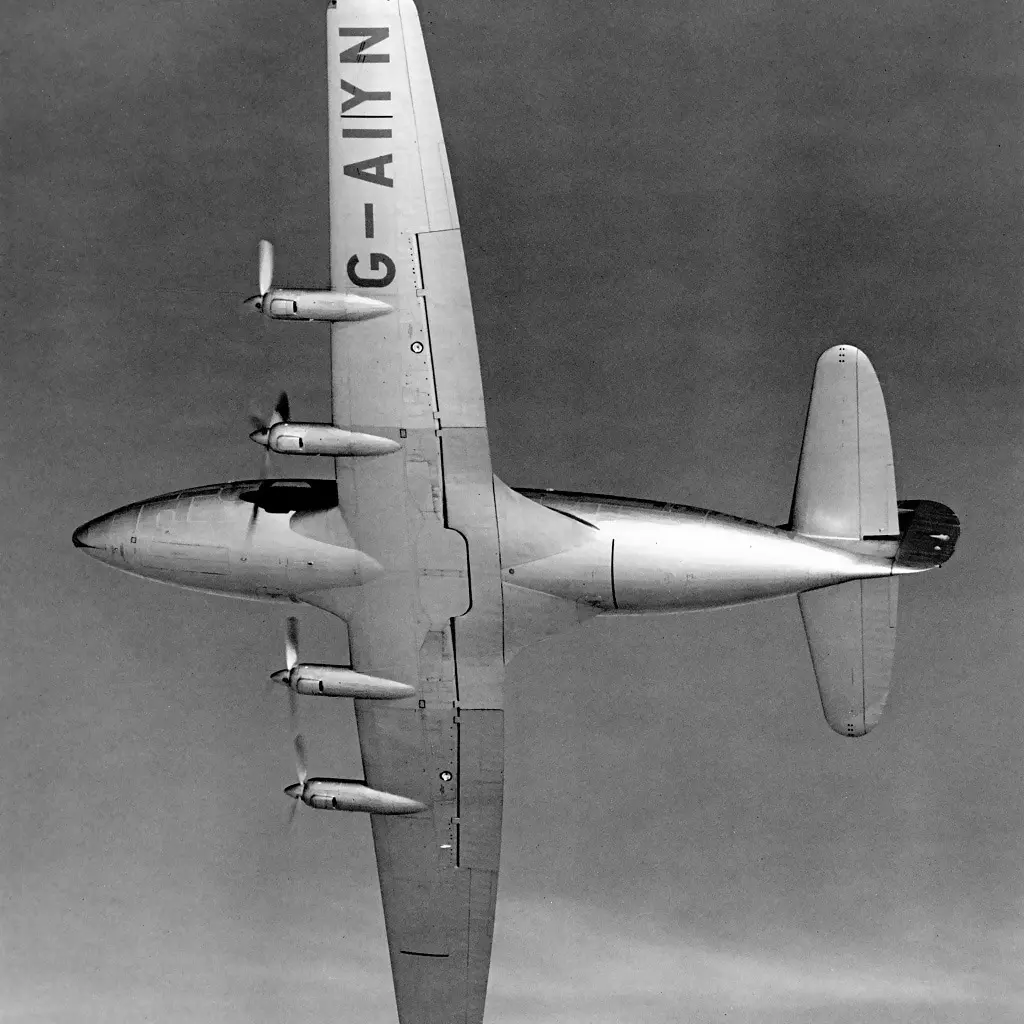

2. Armstrong Whitworth AW55 Apollo ‘Mamba Number 55’

From the majestically batshit, we turn to the elegantly sensible Apollo. The Brabazon IIB requirement was for a turboprop regional airliner of relatively short-range and modest capacity. Two aircraft were developed in response to this, the Vickers Viscount, powered by Rolls-Royce Dart engines, and the Apollo, powered by the Armstrong-Siddeley Mamba. British European Airways, the intended customer, was initially wary of the risks involved with these new turbo-prop engine designs, and ordered the Airspeed Ambassador instead, leaving the Ministry of Supply as the initial customer for both the Viscount and the Apollo.

Development of the Dart proceeded rapidly, with initial flight trials in 1947, and first flight of the Viscount prototype in July 1948. Further development led to series production of 445 Viscounts, with worldwide sales and a long service life.

Development of the Mamba, however proved more problematic. Flight tests of the engine began in October 1947, but the Apollo was not ready for flight until April 1949, and proved to have number of problems with both engine and airframe. Initial flights showed poor longitudinal and directional stability, and modifications were introduced to increase tailplane span and increase fin area. The second prototype, with more powerful engines, flew in December 1952, by which time further development of the Apollo had been cancelled, and BEA had ordered the stretched and more powerful Viscount 700.

So, the Apollo missed the boat, and never benefitted from the increase in power and increase in fuselage length which turned the Viscount into a commercial success. However, the Apollo was a very attractive looking aircraft, and, but for the delays experienced in maturing the engine and airframe, might have been a worthy competitor to the Viscount.

Aircraft combining new airframes with new engines are always a risky proposition, and perhaps the Brabazon Committee over-reached itself in an attempt to differentiate future UK civil aircraft from war surplus US transports. In the event, the Brabazon, Princess, Apollo, Britannia and Comet all paid the price, encountering development delays and unanticipated problems which provided an opportunity for the US to outmatch and surpass all the Brabazon aircraft except the Viscount. Though the rather daft Princess thoroughly deserved its fate, in contrast, the attractive Apollo was unlucky and should have enjoyed a happier fate.

- Jim Smith

3. Avro 722 Atlantic (1952) ‘Vulcan-do’

Flying from London to New York in an airliner based on the Avro Vulcan in less than seven hours would have been a truly remarkable way to travel. Intended for up to 113 passengers, who presumably didn’t mind a bit of noise, the 200,000Ib 600mph Atlantic was not pursued. A bonkers idea from the perspective of economy of operation – but absolutely appealing in terms of delivering noise-loving aesthetes a lovely silver monster. We asked aircraft noise expert Michael Carley his view of the Atlantic and he noted, “If you’re comparing to conventional subsonic airliners, it would certainly be louder than any modern airliner. It would probably have been much louder than any contemporary as well. FAA data taken at Dulles for Concorde and wide- and narrow-body airliners in the seventies have Concorde 10-15dB louder than the other airliners.” Though without reheat, the Atlantic is probably most comparable to Concorde in noise terms.

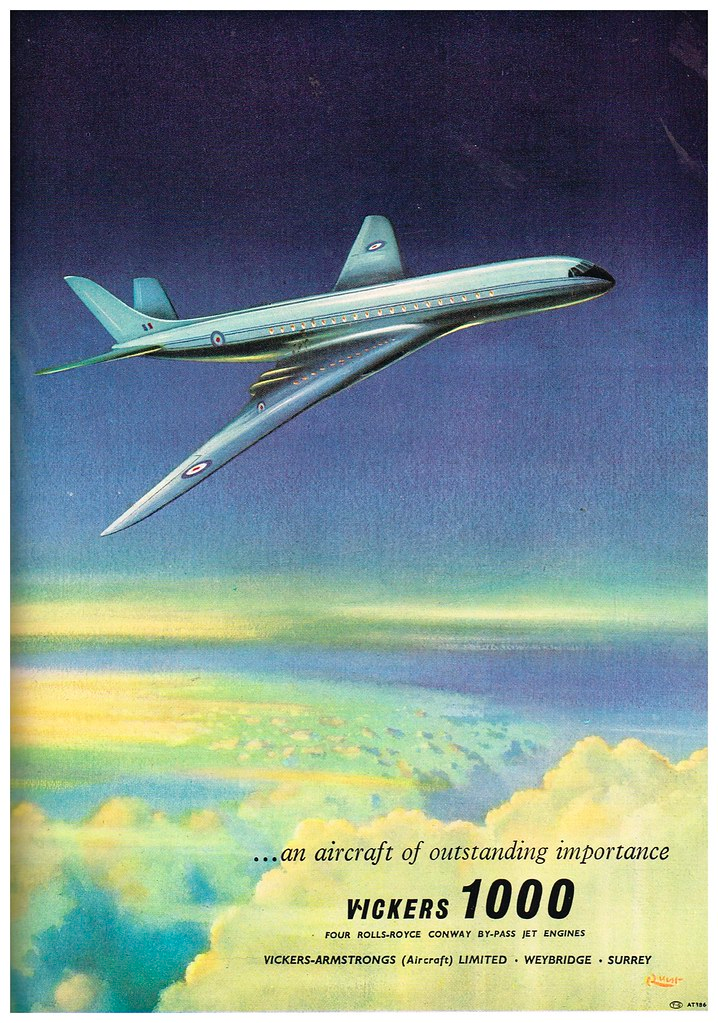

2. Vickers VC.7 (Vickers V.1000) ‘

“I wish this evening to raise the question of what is to me one of the most disgraceful, most disheartening and most unfortunate decisions that has been taken in relation to the British aircraft industry in recent years. I refer, as I think the Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Supply will know, to the question of the cancellation of the contract for the Vickers V-1000 aircraft. My first point is that it is vital to Britain in every sense, in aviation—in the field of industrial work and in the earning capacity of our industry—that we should be able to produce in our home industry a long-range pure jet aircraft which will be capable of coping with the first-class Trans-Atlantic passenger demand. It is, therefore, opportune to ask what are the likely developments in aviation over the next ten or fifteen years in the various aircraft groupings of which we know—the long-range turbo-prop, the long-range pure jet, the medium-range jet and the medium range turbo-prop aircraft? I would have thought that it was almost inevitable that the long-range turbo-prop, which, even today, everyone admits will be able to cope in a few years’ time only with the second-class traffic, will be swallowed up in the relatively near future by the pure jet aircraft. Therefore, the medium-range jet, because of its specialised type of construction and because of the very decided limits of its range, will be superseded in its turn by the long-range pure jet. Meanwhile, the medium-range turbo-prop aircraft which is at present produced and marketed solely in this country will survive, but against inevitably increasing United States competition. The conclusion I draw from these facts is that there is an urgent need for the British industry to be able to produce a long-range pure jet first-class trans-Atlantic aircraft. That can be produced by the British industry and, in fact, there is one potential aircraft available today. If my conclusion is right, that we shall see within the next ten to fifteen years developments to the point where the long-range pure jet aircraft scoops the pool, I would ask my hon. Friend what British aircraft is there which will be available in that period, other than the Vickers V-1000? The Minister of Supply, outside this House, has stated recently that the Vickers V-1000 exists only on paper. Can my hon. Friend tell me where else the D.C.8, for example, exists today except on paper? One reads in the newspapers that there are orders in the region of 200 plus for this aircraft, which exists only on paper. Perhaps, in parenthesis, it is worth saying that of the £2,300,000 that has thus far been invested in the Vickers V-1000 aircraft not one penny has been spent on the civil version except by the firm itself. For a few moments I want to deal with the criticisms which have been bandied about both in public and in private. The most obvious one, of which my hon. Friend will have heard so often, is the weight growth. I understand that the company concerned in making this aircraft originally estimated that the basic weight would be about 96,000 lb. That has subsequently grown to about 112,000 lb. That sounds a rather surprising increase, but in heavy aircraft construction this growth, of about 20 per cent. is nothing unusual. It is in the normal form of aircraft development. There are, however, two points which are highly relevant upon this question. The first is that the weight growth has been completely matched, through the years, by an equal growth in the engine power needed to get this aircraft into the air”

- Paul Williams (Sunderland, South) (Hansard) debated on Thursday 8 December 1955

Britain got extremely close to producing the first big transatlantic jet airliner in the world with the VC7. This would have been a civil spin-off of an RAF transport loosely based on the Valiant V-bomber. The military transport, the V.1000, would have supported the global deployment of V-bomber force, to fly in spare parts and crew at the same great speed and with convenient parts commonality with the Valiant. It would have incorporated the latest propulsion technology, the turbofan (a turbojet featuring a ducted fan) offering less noise than the turbojet, and greater efficiency at subsonic airspeeds. Turbofans have since become de rigueur for airliners – so Vickers were clearly backing a winner. Many have agreed that the cancellation of the V.1000 and so VC7 was a killer blow to large British airliners, but the later VC10 would show that the national predilection for unnecessary short field performance and Boeing-loving airlines were equally powerful forces acting against the success of a British ‘Jumbo’. British aircraft of this time often prioritised aerodynamic efficiency of maintainability and the VC7 with its sleekly buried engines, would likely have been another example, not to mention how difficult it would have made the retrofitting of later larger engines.

- Hawker Siddeley Aviation Type 1011 ‘The Supersonic Sex Tiger’

An orgasm of sleek aerodynamics, the 1011 was one of the few aeroplanes so attractive that it could have gone to a bar with Concorde and not be overlooked as the plain plane friend. Designed to be barely supersonic (M1.15 at full tilt) to avoid the overland route limitations of sonic booms, it nevertheless employed an extremely bold form calling to mind the fictive Carreidas 160 from the Belgian comic book Tintin’s Flight 614.

A seductive blend of a delta t-tail, sumptuous curves, sword-like variable geometry wings and four high bypass ratio Rolls-Royce RB 178/1B turbofan engines pumping out a combined 100,000-Ibs of thrust would have created an utterly charismatic aeroplane. But it would have also have been extremely maintenance heavy while offering a marginal, rather than transformative, reduction in journey times. Still, one can dream.

“Geoff Richards worked on the aircraft and commented to Hush-Kit, “Brings back a few memories. I joined HSA’s Advanced Projects Group straight from college in 1966. At the time the 1011 was on the back burner and the main interest was the military 1034. It was around 1971, I think, that there was a bit of renewed interest in the 1011 and I was tasked with seeing if the wing design could be improved with Robin Lock’s new aerofoils, as indeed it could. That was the last hurrah for the project, as shortly afterwards APG lost the projects part of its remit and was reassigned to manage HSA’s research work. The basic idea of avoiding sonic boom was certainly OK, but the complexity associated with an area-ruled passenger cabin and the relatively small speed advantage were against it. The fact that no-one else has tried the idea speaks for itself.”

Further excellent reading on the 1101

You can boast/complain/rant about knowing types not on this list in the comments section though I may take some time to approve these as I’m working through a large backlog of comments.