Despite over 800 being built, today the Nakajima Ki-49 bomber remains out of the historical limelight. Appropriately for such a seemingly introverted machine, it was assigned the almost comically innocuous codename ‘Helen’, after the wife of an Allied intelligence officer in the Pacific Southwest. In service with the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service and operating in dangerous skies, the type served as a bomber, anti-submarine patroller, transport and even as a kamikaze manned suicide aircraft. Often facing utterly fierce opposition, the bomber had a sting in its tails – and an even more potent one on its back. Often condemned as vulnerable, we asked author George Eleftheriou for the truth about the shadowy ‘Storm Dragon’.

“It wasn’t vulnerable! Would you call the Dornier Do 217 or the Tupolev Tu-2 or the Vickers Wellington vulnerable? Why is it that only Japanese aircraft have this reputation?”

What is the closest Allied analogue to the Helen, and how did it compare?

Rather difficult to answer. Combat-philosophy-wise the Martin B-26 Marauder would be the closest one. A fast medium level bomber that would have been able to conduct raids in lightning speed avoiding getting intercepted by enemy fighters was a common concept in many air forces around the world.

The B-25 Mitchell is a second close but the ground attack role it was largely assigned to in the Pacific did not match the combat deployment of the “Donryuâ€. With only a 7.7-mm flexible machine gun in the nose, it simply could not do any serious strafing attacks like the Mitchell could.

The US B-26 Marauder had a maximum speed of 287mph and the Mitchell even less, at 272mph. In theory, Helen was faster than both, with a spritely top speed of 305mph. That’s only on paper, of course. In reality the “Donryu†(Storm Dragon) was much slower, with a max speed never exceeding 400km/h as beyond that, the engines badly misbehaved. As it was equipped with engines of only 1410 horsepower engines, compared to the hefty 2000hp and 1700hp of the two US bombers, this speed could only be achieved by sacrificing the bomb load. “Donryu†could carry a ton of bombs while the US bombers could carry almost double. In the Pacific Theatre, where most combat took place over jungles, big bombs did not really matter. Where they mattered most was against ships. Therefore, Helens, like Mitchells, normally carried 50kg bombs and quite often cluster bombs. But the extra ton the US bombers carried meant higher destructive capability and success rate.

What was the best thing about it?

The Donryu was the first Japanese Army bomber with a tail gunner operating a 7.7mm machine gun. An improvement over the Mitsubishi Ki-21 “Sally†that only had a remotely operated machine gun on the tail. But in any case, the role of the tail gun was to force the enemy fighters out of this vulnerable blind spot and into the sights of the heavier and more destructive 20-mm cannon Donryu had on its dorsal position.

And the worst?

I would have to say its engines. Underpowered, difficult to maintain and prone to breakdowns.

How many were lost in combat, and to what causes?

Difficult to answer. No loss statistics by the Japanese Army have survived, if any were kept. Model 1 Ki-49s were retired once Model 2s became available and they were assigned to some flight schools in Japan and probably to a few transport units. It could be said that most Model 2s, the model that saw the most combat, were shot down but a good number was destroyed on the ground by Allied bombing raids.

Was it based on another design or was it developed into another type?

Neither. It was an original design by Nakajima and there was a small number of models and test aircraft but it had no successor.

What was its most important historical contribution?

None I know of. The tail gunner maybe?

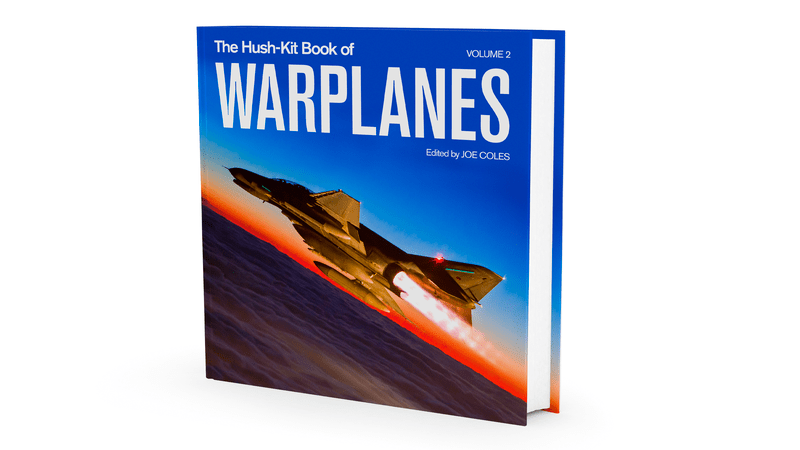

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes Vol 2 is fully funded and can be pre-ordered here. It will feature the most exciting accounts from air warfare from World War II to the modern day. Expert analysis, satire, pilot interviews, top 10s, beautiful artwork and worldclass photography. Big, glossy and entertaining, it is the must-have military aviation book. Read Amazon reviews of book 1 here.

Who used it?

Unlike Allied aircraft types that were operated by different nations, it only saw action with the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force. If you’re asking about units, the 7th, the 61st, the 62nd, the 74th and the 95th Sentai were the primary units that flew the type.

(Ed – I believe it did have some post-war use by the French in Indochina, with Indonesian guerilla fighters and as a transport with the Royal Thai Air Force though I’m happy to be corrected if wrong)

What was its worst operational experience?

If you’re talking about combat missions, then it must be the loss of eight 62 Sentai Donryu and one damaged during a single raid against Ledo, Assam, India, on March 27, 1944.

Another unpleasant experience was the loss of nine 74th Sentai “Donryu†and four seriously damaged during a ground attack raid by US Navy aircraft in Luzon, the Philippines, on November 19, 1944.

Why was it so vulnerable?

It wasn’t! Would you call the Dornier Do 217 or the Tupolev Tu-2 or the Vickers Wellington vulnerable? Why is it that only Japanese aircraft have this reputation?

Would you say it was the worst Japanese aircraft, and is that what interested you about the aircraft?

It was definitely not the worst Japanese aircraft. There were other types with higher attrition rates, like the Mitsubishi G4M ‘Betty’ and technically speaking the much venerated Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa with its meagre 7.7mm machine guns was completely obsolete by the time it started to be produced.

Perhaps this kind of infamy was stuck to the Donryu because it has been considered an easy-to-shoot-down type. But contrary to non-Japanese sources, many Donryu that are counted as “kills†by Allied fighter pilots, did manage to bring their crew back to base.

Its engines left much to be desired and therefore it can be said that it was not a good aircraft. It was definitely not an overall improvement over the older Mitsubishi Ki-21 Sally except for a few features like the tail gun and the 20-mm dorsal cannon.

But as the reader can find in the Osprey publication, the crews who had no previous experience with the Sally and therefore couldn’t compare the two types, were not particularly unhappy with the aircraft and did their best with what they had. For example, the crews and bombers excelled during night missions. As explained in the book, most Helen losses were caused by miscalculation, bad tactics or simply bad luck. For sure, more powerful and reliable engines would have resulted in a much better aircraft but I cannot say the Donryu was a death-trap. At best it was a mediocre type that, in my opinion was placed into production to appease Nakajima after its original design was ‘borrowed’ by Mitsubishi to produce the Sally. But objectively speaking, Nakajima always had issues with its engines, whereas Mitsubishi produced better ones and therefore superior aircraft. It was the mindset of the Japanese Army (and Navy) compounded by the technological limitations of the Japanese industry and the reality on the ground that failed to provide the Japanese bomber crews with better really heavy bombers.

Much has been debated as to why the Japanese (and the Germans) never put into production a really heavy four-engined bomber. Both the Sally and the Helen were developed as fast bombers with the possibility of a war against the USSR in mind and combat operations in Siberia where no industrial centres or other major targets existed. Therefore the bombers were designed to quickly attack troop concentrations and fortifications, mirroring similar German tactics. When the Sino-Japanese War broke out, the bombers were assigned to exactly these roles and occasionally attacked cities aiming mostly on military targets rather than conducting carpet bombing that was later employed by the Allies.

Similarly during the Pacific War, Japanese bombers targeted enemy troop concentrations closely liasing with the infantry. Strategic bombing was never necessary since there were no appropriate targets. The Japanese Empire wanted to capture the oil fields of South East Asia and put them to use, not destroy them. In the opening days of the war, Allied held airfields were not targeted; the enemy aircraft found on them were. Because the airfields were expected to be captured by the advancing infantry and then be operated by the Japanese aircraft.

Running the Hush-Kit site takes a lot of effort. If you wish to see this site carry on please consider making a small (or large) donation. Reccommended donation £12.00. Every donation is greatly recieved. Donate here and be part of our story. (In case my WordPress skills are not good enough and this link won’t work, please use the button below and to the right)

When the need arose for really heavy bombers, such as during the attacks against the Allied bases in Assam or later during attacks against bigger bases that were built by the Allies like on Morotai Island and Leyte, that’s when the Japanese industry and technology failed to deliver, mostly because it lacked experience with four-engine designs (except for flying boats). In any case, newly delivered four-engined heavy bombers would have created new challenges, requiring bigger and better constructed airfields and more efficient logistics to support heavier bomber operations. The Japanese could barely supply enough fuel for their Helen and Sally-equipped bomber units and never got even close to the logistic capabilities of the Allies.

The Helen, like many other Japanese aircraft types, has this reputation of being a bad aircraft that was vulnerable and quickly shot down by Allied pilots. The more I delved into original Japanese sources, like testimonies from bomb crews, the more I realised that the complete story has not been told and that inspired me to write this book with Osprey.