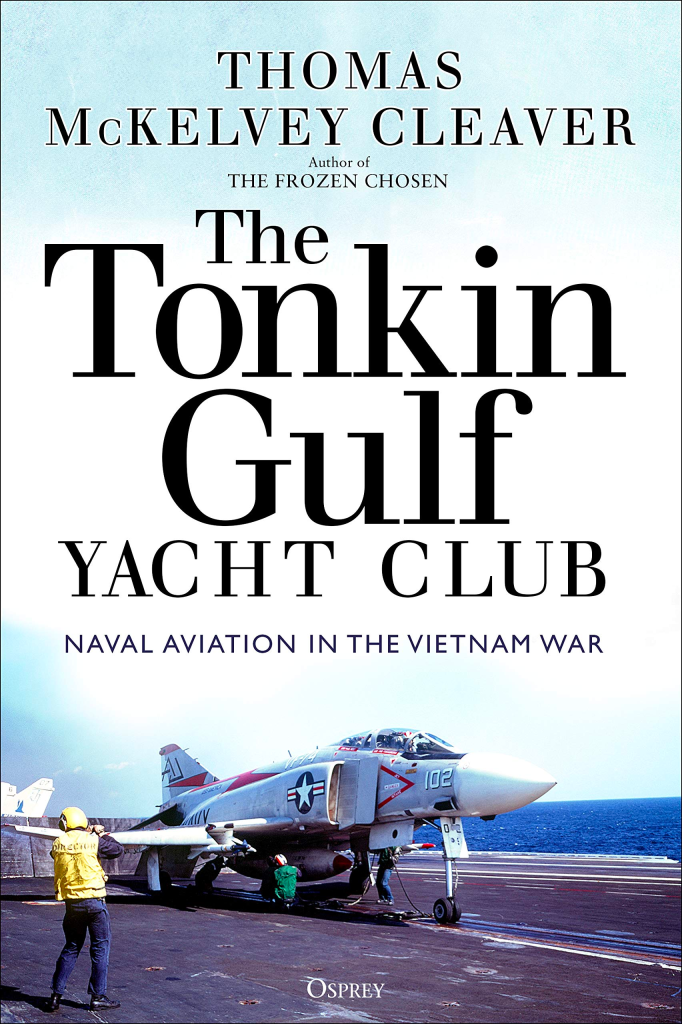

Extract from The Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club (courtesy of author and Osprey Books)

As for many of my generation, the war in Vietnam and my participation in it changed my life completely. Forever.

- Thomas McKelvey Cleaver

Looking back, I divide my life in two parts: Before Tonkin Gulf, and After Tonkin Gulf. I will never, ever forget the moment in late September 1964, when I decided to stop in a bar on the main street of Olongapo, the “service town†outside the Subic Bay Naval Base, that I was passing to get out of the tropical sun. USS Pine Island, an ungainly seaplane tender that was flagship for the admiral’s command, of whose staff I was an enlisted member, had docked that morning for a break after our first deployment to Da Nang, following what we all knew was the first step to a war in Vietnam that involved us – the “Maddox Incident†as we in the Navy called it.

Inside, sitting at the bar, was my best friend from Navy boot camp, who I hadn’t seen since we had both gone through firefighting training at the San Diego Naval Station the year before while awaiting transport to our separate destinations in WestPac. His ship’s patch was on his shoulder: “USS Maddox.†I’d forgotten that was his destination.

Taking the seat to his left, I took note of the outline of the missing petty officer’s “crow†on his sleeve. The outline of holes where the crow had been sewn told its own story – he’d been busted. Recently. I bought us each a San Miguel, and answered his questions about what I’d been doing: I worked in the operations office on the staff of Commander Patrol Forces Seventh Fleet, which I noted had been Maddox’s operational commander at that event. He frowned at that. Another round of San Miguel was ordered, and it was my turn to question him. As delicately as I could, I asked “How’d that happen?†pointing at his sleeve.

“Got busted.â€

I expected him to tell me he’d gotten a “captain’s mast†for coming back late from liberty, something that could happen to any of us and nothing to make a big deal of. No. He’d been court-martialed. Hmmm – a summary court was a little more serious, so I asked “what for?â€

“Failure to obey a direct order.â€

Now that was serious indeed.

“What order?â€

“‘Open fire.’ Said ‘no’ three times.†Yikes!

And then, while he told me there had been no enemy torpedo boats attacking Maddox or Turner Joy that night I’d been awakened at 0200 hours as the duty yeoman in the operations office to take the FLASH message of the attack to the Chief of Staff, how he had been the senior fire control technician in the ship’s gunnery control tower and had three times refused to open fire with the six 5-inch guns he controlled, telling his captain each time that the only target out there in the darkness was the other American destroyer, my life changed forever.

Never again, after those minutes in that Olongapo bar, would I ever believe without proof anything said by any official of the government of my country, a country whose constitutional government I had sworn to protect against all enemies, foreign or domestic. Little did I know then that, after I got home the following year and returned to civilian life, I would spend the next seven years consumed by my opposition to the war I had learned that day was a lie.

I came to learn during those years that there is a profound difference between loving one’s country and supporting its government.

I have studied the Vietnam War in detail in the years since I returned home and told my father that first night back that “You know absolutely nothing about what’s really going on in that war.†That was the beginning of the Seven Years’ War of the Cleavers – with my father finally saying in 1987 that I had been right, during what turned out to be our last face-to-face conversation. It’s why I spent a considerable bit of time in the late sixties involved with the late Dr. Peter Dale Scott, who was dedicated to tracking down the witnesses to the lie that began what had come to be known as the “War of Lies†and discovering that what I had discovered that afternoon in an Olongapo bar was almost only the least of it. It’s why I ended up with a degree in History. It’s why I was overjoyed the day I laid hands on a copy of the “Pentagon Papers,†where for the first time I read an account of the event that changed my life that comported with the reality I had discovered.

It turns out that even now, 50 years later, there are secrets from that night still to be examined. Others have studied the Tonkin Gulf Incident, and it is now known that those “lights in the water†mistakenly identified as enemy torpedo boats were in fact the reflections of the moon and lightning flashes on the enormous school of flying fish that transits the Tonkin Gulf at that time of year. Lyndon Johnson was more right than he knew when he exclaimed, on being first informed of the event, that “those dumb, stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.†In that moment, he knew more about the war than all his advisors ever did.

One can nowadays ask Google the right questions, input an old code name, and be rewarded with a PDF of a document previously classified Top Secret, now declassified through the Fifty Year Rule, and find that they knew! They knew all the mistakes, all the missed opportunities, everything! They knew them and either let them continue or took actions that exacerbated them.

Perhaps the best news to come from that war is that the men who were in the cockpits of the MiGs, and their opponents in the cockpits of the Phantoms and Crusaders, have come to know each other personally, have visited each other in their homes, have become friends. They recognize and respect each other. Peace has been declared.

This book could not have been written without the active help of those who were there: Rear Admiral H. Denny Wisely from Fighter Squadron 114 (VF-114) and the war’s first years, Captain Roy Cash, Jr., who served in VF-33 in the middle years, and Commander Curt “Dozo†Dosé of VF-92 and Lieutenant Michael M. “Matt†Connelly of VF-96, who flew in 1972’s “new war.†Their willingness to go over their experiences in detail and to review the manuscript for accuracy was critical to completing this project. The late Don Davis, the Associated Press war correspondent who originally reported the “Higbee Incident,†provided essential information on the event that the Navy’s History and Heritage Command now claims never happened. Rear Admiral James A. Lair of Attack Squadron 22 (VA-22) as well as Captain Ken Burgess, Captain Timothy Prendergast, and Captain Richard Heinrich of VF-51, Lieutenant Commander William Crumpler of HC-1, and Admiral James W. Alderink, then commander of Air Group 21 aboard the USS Hancock, recalled their experiences during Operation Frequent Wind, the evacuation of Saigon in 1975, and the Mayaguez Incident.

Importantly, through Roy Cash and Curt Dosé, I was also put in contact with retired Lieutenant General Pham Phu Thai, who ended a 30-year career as deputy commander of the Vietnam People’s Air Force (VPAF), and retired VPAF Colonel Tu De, the last living participant in the Higbee Incident, who shared their experiences as young pilots of “the other side.†Dr. Nguyen Sy Hung, Historian of the VPAF and author of Aerial Engagements in the Skies of Vietnam Viewed From Both Sides, considered by American participants who have read it to be a far more accurate and honest account of events they were party to than official US sources, provided an English translation of this important book, without which it would not have been possible to write a history that puts both sides in the air together. After 50 years, it’s time to try to tell the whole story.

Examining any facet of the Vietnam War inevitably leads to the question, “Were there any lessons learned?†Sadly, a five-minute examination of the daily paper can quickly lead to the answer: no, no lessons were learned.

If there is a lesson, it is this by foreign policy analyst Adam Garfinkle, analyzing Vietnam and our wars since:

Finally but most important, U.S. expeditionary forces operating in any non-Western cultural zone are very unlikely to win a war at reasonable cost and timetable, employing levels of violence acceptable to the American people, unless the U.S. effort includes a serious effort to understand the country, and unless it has a local ally that is competent and legitimate in the eyes of the population it would rule. In none of these cases did those conditions apply.

This book is for those who cannot forget this history.

The Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club: Naval Aviation in the Vietnam War available here

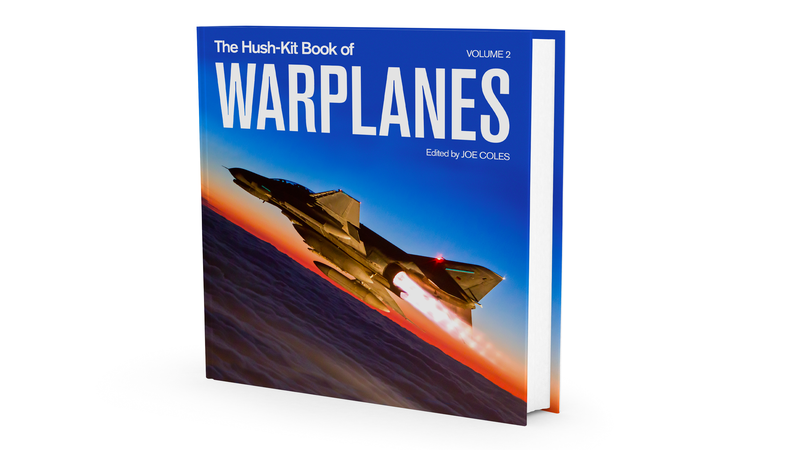

The Hush-Kit Book of Warplanes available here and volume 2 can be pre-ordered here