“Everyone will sit on a little donkey.”

-Yugoslavian proverb

The young nation of Yugoslavia, formed in 1918, leapt into the creation of aircraft with great zeal. Sadly, most of their aircraft industry was smashed to pieces in World War II, with factories destroyed by both Axis and Allied actions, and many of their aircraft designers intentionally killed by retreating German forces. Liberation by partisans led by Josip Broz Tito, ushered in a new aligned communist nation quite unlike any other. Yugoslavia’s often brilliant aeroplanes were often every bit as unusual as the nation’s geo-political position. With great confidence Yugoslavia embraced the jet age with unorthodox thinking and great ambitions, including a plan for a fast, bird-winged nuclear armed strike jet. This last project cannot be included in the list as it never progressed beyond a bizarre unpowered glider, the Ikarus 453MW seen above and below.

10. Aeroput MMS-3 (1936) ‘Spirta’s burning superstar’

A tiny transport, training and utility prototype, the Aeroput MMS-3 was designed by Milenko Mitrovic-Spirta. Spirta had dreams of the MMS-3 becoming a mass produced air taxi, neatly carrying three passengers (or air mail) in the gondola-like fuselage slung under the wings. Military roles were also considered but were thwarted by the Axis invasion of 1941. Unlike most twin-boom, twin-engine aircraft the MMS-3 had only a single vertical fin mounted at the centre of the horizontal stabiliser. The MMS-3 was pleasant to fly with excellent aerodynamics qualities and a gloriously unobstructed view from the cabin. Power came from two 7-cylinder Pobjoy Niagara III geared radial engines which were smooth, quiet and economical. Sadly, there was just too few resources available for developing this excellent machine. Mitrovic-Spirta personally set the only example on fire in 1941 to keep it out of German hands.

Think of it as a bit like: a Willoughby Delta-8.

9. Rogožarski SIM-XIV-H (1938) ‘The RAF’s finest Yugoslavian‘

How many aircraft of Yugoslavian origin served with the RAF? At least one. The SIM-XIV was a coastal patrol, light bomber and reconnaissance floatplane commissioned for the Royal Yugoslav Navy. Like the IK-2 and IK-3, it was part of a too-little-too-late scramble to respond to unpleasant military contingencies. With barely 500-horsepower from a pair of Austrian-made Argus V-8s, limited bombload and only two rifle calibre machine guns, it’s surely small wonder the SIM-Xi Vs made very little impression on Yugoslavia’s attackers in 1941. In a rather epic escape, two (of four that tried) managed to flee to Greece, then Crete, then onto Egypt after most of their sister aircraft were wrecked or captured. The RAF put this pair briefly into patrol service adding an early, if deeply obscure, line to the record of captured aircraft during the Second World War. The modest SIM-XIV was an attractive machine that could have made it onto any top list of pretty 1930s aeroplanes. It also had wings consisting of wood structures under plywood skinning, and a distinctive greenhouse type nose incorporating a non-powered turret.

Think of it as a bit like: a smaller version of the Bristol Fairchild Bolingbroke Mk III with half the horsepower.

8. Fizir F1V ‘Brza koza’

The Fizir F1V was a neat reconnaissance biplane with equal span wings and two seats. Fresh off the drawing board it won an international endurance race in Poland in 1926. The F1V was Intended to replace a battered wartime fleet of mainly French and German designs, and was the equal of any in the world; considering the backdrop of financial constraints and general upheaval attendant to the country’s emergence, this is an extremely impressive achievement. But things wouldn’t be easy for the Yugoslavian aviation industry, which was often beset with bad luck and awkward geo-politics. Engines would be a particular problem, requiring advanced manufacturing and engineering skills that strained the new country’s ability to deliver what a modern air force needed. The sound, relatively clean airframe of the F1V would have to be mated to a half dozen imported or license-made engines including Maybachs, Bristols, Wrights, Hispano-Suizas, Walters and Lorain-Dietrichs. Fifty-six F1Vs were built for training and scouting roles with a handful still in service in 1941.

Think of it as a bit like: a D.H. 60 Cirrus II.

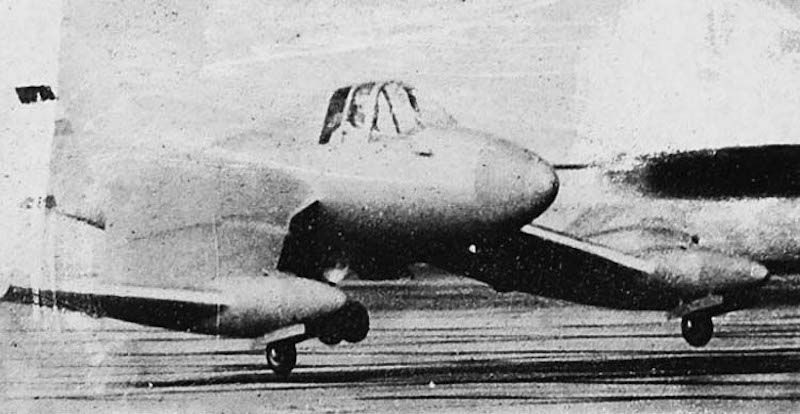

7. Ikarus 451 M (Mlazni or Jet)

The 451 M was never intended for production. It was a developmental platform for an industry trying to grapple with new technology and a difficult national situation with uncertain resources. Despite looking (eventually) like a Lilliputian mash-up of a Jet Provost and a Me 262, the 451 M can be considered a success. It started life in 1951 with two Walter Minor piston engines and an airframe developed for a prone pilot project, but somehow successfully transitioned to a jet propulsion demonstrator. French-sourced turbines were swapped for the Walters and an underside fuselage fairing for a 20mm cannon was added as well as wing mounts for unguided rockets. This aircraft demonstrates the imagined maxim that if you are going to be an obscure, experimental warplane you must have the most elegant tail profile you can afford. The inclusion of braced elevators among other features, gives this a prewar rather than space age flavour. While cute from some angles, this aircraft could pass for one of the desperate projects from the last days of the Third Reich.

Think of it as a bit like: some some American brewery’s micro-jet from the early 1990s.

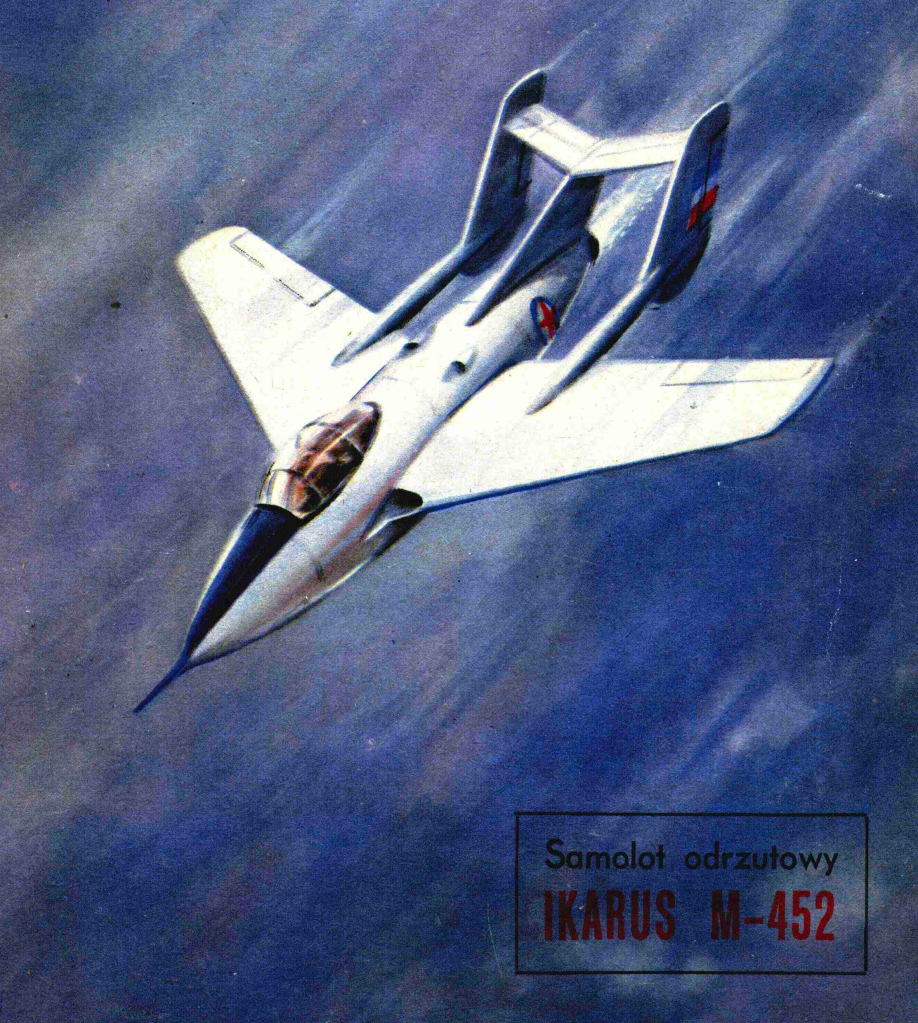

6. Ikarus 452 (1953) ‘Micro Sea Vixen’

We thought the only jets to employ the stacked engines arrangement were British Lightning and the French Sud-Est Grognard, but the plucky Ikarus 452 is also a member of this unusual club. Wait, shouldn’t we include the Short Sperrin?

Just to add to the fun it was a twin-boom job with a double set of air intakes for its paired Turbomeca Palas 056A turbines. As you may have guessed from the photo, one engine is fed air via wing root intakes and the other by intakes mounted on the fuselage sides. A newly developed metal alloy was used throughout the 452’s structure and despite having only about 700 lbs of thrust it was fast enough to justify fully swept wings and a swept horizontal tail. Two or four .50 cal M3 BMGs were its planned armament. Only two were ever built as they were designed only to gather engineering experience for application to future warplane projects which came to include the Galeb, Jastreb and Super Galeb.

Think of it as a bit like: pretty much nothing else.

5. SOKO G-4 Super Galeb (1978)

A hotter version of the Galeb, the Super Galeb had greater thrust and better avionics than its predecessor. The Super Galeb has stepped seating offering the rear seat instructor a better view. Swept wings and a much reinforced structure were provided to accommodate a heavier armament load and the more powerful version of the Rolls-Royce Viper than is found in the Galeb. Serbia’s post-1990s air force has rebuilt itself in part on the Super Galeb with upgrades set to keep the type valid into the 2030s. The collapse of Yugoslavia saw numerous Super Galebs destroyed by AAA or Nato F-16s. Trade embargoes, not to mention the general difficulties arising from a civil war, hampered production and prevented meaningful export sales of Super Galebs during the 1990s and early 2000s.

Think of it as a bit like: Aero L-39 Albatross or the IAR 99 Soim.

4. SOKO G-2 Galeb / J-21 Jastreb (1961) ‘

The Galeb was a trainer and light attack jet designed to replace the T-33 Shooting Stars supplied to Yugoslavia through the United States under their Military Assistance Plan. A shade smaller than the Shooting Star, the Galeb was actually inferior in performance. The Galeb used a licence-built copy of the Rolls-Royce Viper engine which provided barely half the thrust of the T-33’s Allison J33, hence, the 600 mph maximum speed of the American jet and the comparatively sluggish 470 mph maximum speed of the Galeb. Its other performance metrics were similarly mediocre. In the attack role, payloads were paltry compared again to the T-33 or other similar designs like the Aermacchi MB-326. Nonetheless, 250 Galebs were built at the SOKO plant in Mostar beginning in 1964. Designed with significant components from the UK’s aircraft industry (ejection seats and instrumentation as well as powerplant), the Galeb is Yugoslavia’s only real warplane export success story. Libya, Zambia, and Indonesia placed orders for the Galeb.

As Yugoslavia disintegrated, both aircraft types saw frequent action on behalf of Belgrade or of breakaway republics. Many G-2s and J-21s were destroyed by AAA, air-to-ground weapons or NATO fighters. Only a handful of either type remain in service in successor states. Galebs and Jastrebs saw employment in the First Congo War on behalf of tyrant Mobutu Sese Seko and during the Libyan Civil War in 2013.

On a brighter note, pilots and ground technicians reported the Galeb and Jastreb were easy planes to work with in absolutely every respect. A handful of Galebs have found their way into private hands as aerobatic display and training aircraft. Warbird collectors in Europe and North America own several Galebs. At the time of writing there is one for sale in Slovenia for $US82,000 which is near the cost of a luxury Sport Utility Vehicle.

Think of it as a bit like: a BAe Hawk or Fouga CM.170 Magister.

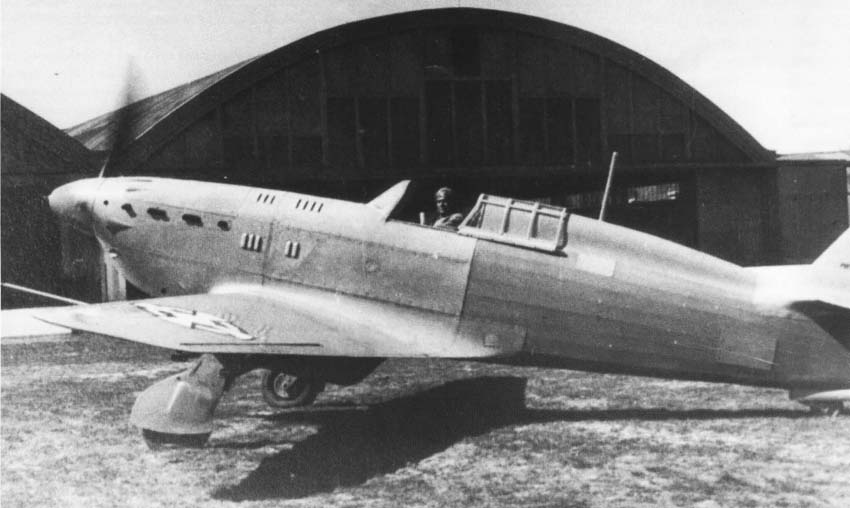

3. Ikarus IK-2 (1935) ‘The relic’

Without huge technical assistance from France this fighter programme would have yielded even less – and it did not achieve much at all. The result was a dozen examples of a largely obsolete aircraft. France offered training to the IK-2’s designers and gave them access to wind tunnel facilities. French engines, auto-cannons and machine guns were also to be incorporated. Initially based on an airframe of mixed construction reminiscent of the Hawker Fury, the IK-2 was redesigned with an all-metal airframe. So far, so good, right? Unfortunately, like other fighters under development in eastern Europe, the IK-2 remained ”old school” enough to make it only marginally acceptable against future possible enemy aircraft being made elsewhere. Evidence of that is seen in the complicated strut work attaching its fixed main landing gear to the fuselage. Yugoslavia was simply not rich enough or industrially developed enough to come up with anything near the Messerschmitt Bf 109 Dewoitine D.520 on its own. To contrast that Poland built some 325 of its similar PZL P.11s while Yugoslavia barely managed a dozen IK-2s.

While the high-wing monoplane IK-2 offered excellent manoeuvrability, it was no match for modern low-wing monoplanes with retractable undercarriages and 1000 horsepower engines, multiple autocannon and machine-guns. Though nimble in prewar testing, the IK-2 would never match more advanced peers. They were swept aside in 1941. They do, however, deserve a number 3 place for being so very attractive.

Think of it as a bit like: a Dewoitine 371, the PZL P.11 or an Avia B-534.

2. Ikarus S-49C (1949) ‘Monster Yak’

The S-49C was a further development of the IK-3. It came from the same design team immediately after the war. They had been encouraged to utilize a powerful, war-proven Soviet engine, the Klimov VK-105. This engine had been put into the premier Soviet fighters of the war like the LaGG-3, Yakovlev Yak-1, -3 and -9 and even the Petlyakov Pe-2 light bomber. With that powerplant, the S-49 might have been a considerable fighter along the lines of the last generation of piston-engined machines from the West or the USSR. Alas, the split between Stalin and Tito in 1948 saw Yugoslavia cut off from Soviet technical support. The S-49’s designers turned once again to a (less powerful) Hispano-Suiza engine, the 12Z. Curiously, the IK-3’s prewar Oerlikon 20mm was replaced by German-made stocks of Mauser MG-151s supplemented by American .50 calibre BMGs. For the C version, mixed construction was replaced with an all-metal design that needed a longer nose to accommodate the heavier French engine. The S-49C was what the IK-3 maybe could and should have become had Yugoslavia not been invaded and occupied. As the jet age dawned and Yugoslavia attempted to find its feet it was perhaps simply the best option available for a country, and an air force, in a bad position. Performance, with a top speed of 390mph, was better than the IK-3’s but the S-49C didn’t compare to the likes of the Hawker Sea Fury, let alone turbojet fighters.

Book review here.

Think of it as a bit like: an Avia S.199 or Hispano Aviacion HA-1112.

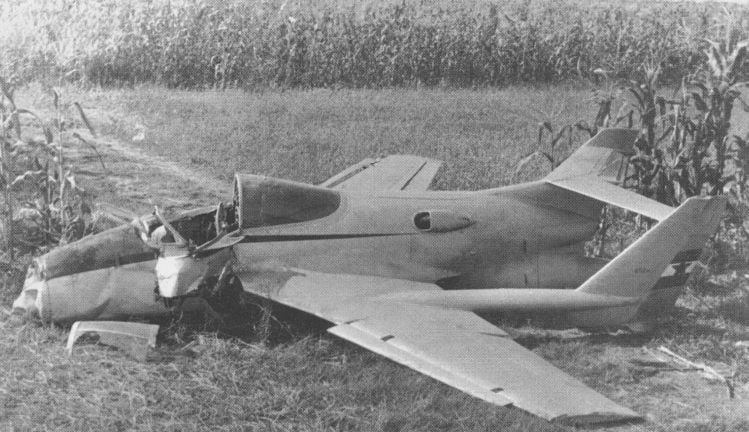

- Rogožarzki IK-3 (1938)

The IK-3 typifies the fatal entanglement of aspiration and limitation typical of the first two decades of Yugoslavian aviation, and so heads grabs the number 1 slot in our list. The fact it looks like a Hurricane caught midway crashing through an Anderson shelter furthers our love for this characterful fighter.

The IK-3 was the country’s belated attempt to arm itself with a domestic single-engine monoplane fighter, and one that might have a had a fighting chance against potential adversaries. In terms of performance it was hoped the IK-3 would come out at least equal to the Hawker Hurricane I. Official testing found it close to the Hawker Fury biplane, which was in Yugoslav Royal Air Force service alongside the Hurricane, and, wait for it, the Messerschmitt Bf 109. To cut the cost of developing a fighter engine from scratch, the Yugoslav authorities commissioned Avia in Czechoslovakia to supply license-built copies of the Hispano-Suiza 12Y engine. This liquid-cooled, boosted V-12 was good for about 860 horsepower on takeoff. In the IK-3’s mixed construction airframe this engine offered a maximum speed of 327 mph and a time to 16,000 ft of seven minutes. This was pretty good in 1936 when the IK-3 was on the drawing board but not good enough by mid-1941. Combat, seizure and sabotage took care of the dozen IK-3s built before calamity enveloped Yugoslavia. Their defiant pilots managed to destroy a handful of bombers and at least one Messerschmitt Bf 110 in the early days of the invasion. Alas, air power in a moment of national disaster is rarely served with the right designs.

Think of it as a bit like: a Moraine Saulnier M.S. 405.

– Stephen Caulfield