Why are almost all warplanes grey? We wanted to know more, so we approached the RAF Museum.

Grey is a miserable colour. It is the colour of desolate industrial areas, the sky on an unlovely Tuesday afternoon in England, or else the tone of faceless bureaucracy or unhappy vagueness. According to colour historian Eva Heller, “grey is too weak to be considered masculine, but too menacing to be considered a feminine colour. It is neither warm nor cold, neither material or spiritual. With grey, nothing seems to be decided.”

It is among the least popular colours – that is outside of the field of combat aircraft paint-schemes. In other times, warplanes were painted brilliant blue, left in the glorious shine of unpainted aluminium or resplendent in jungly green camouflage. Then everything went grey. Even the roundels –– those once colourful markings that show you which air force is operating the machine flying past – became washed out.

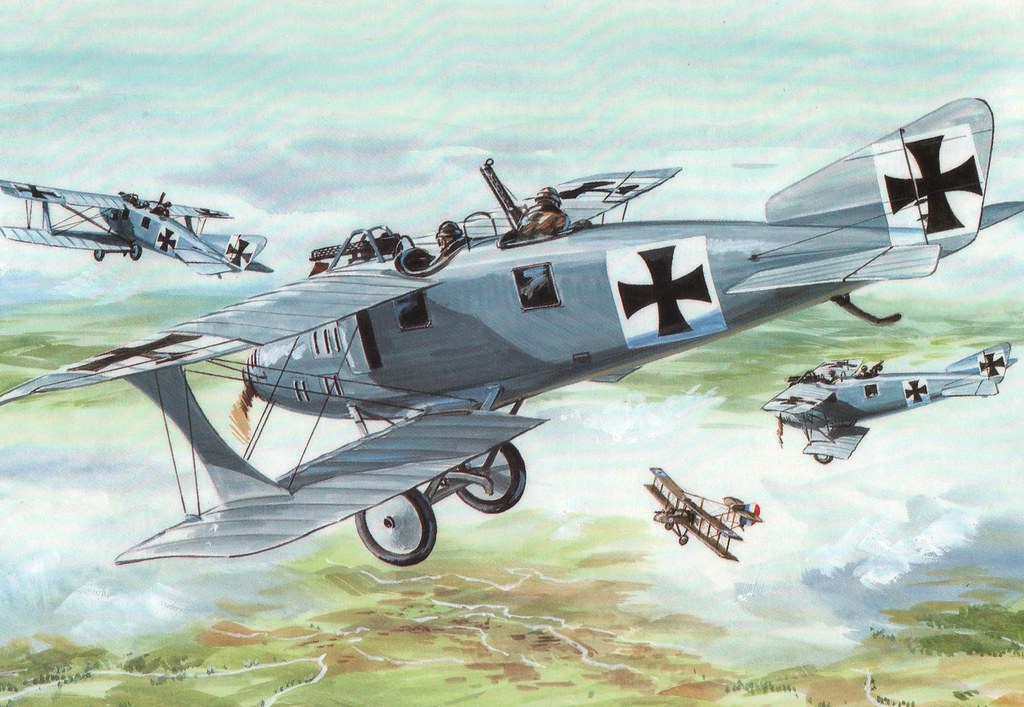

First World War origins

It was in the First World War that the application of camouflage became virtually universal for armed land forces, partly due to the threat of aerial reconnaissance. Likewise, aircraft needed to hide from each other, from anti-aircraft fire, and from being spotted on the ground by enemy aircraft while on the ground. Various schemes were used including the very distinctive German lozenge pattern, all-over olive green and even the application of transparent fabrics. Grey was also used. It is perhaps unsurprising, as grey (or grey-blue) already had a strong military association for ground forces. Early 19th century firing trials in Austria concluded that grey was a more effective camouflage for soldiers than green. A study carried out by Captain Charles Hamilton Smith came to the same conclusion in 1800: grey was a better than green at “a distance of 150 yards.” (advice ignored by the British Army which instead opted for green).

Grey dyes were also inexpensive and easy to manufacture, something pivotal to the adoption of grey uniforms within the Confederate forces in the American Civil War. The German Army wore feldgrau (‘field-grey’) uniforms from 1907 right up until 1945, chosen for their camouflaging qualities at great distances – something that had increased in importance with a new generation of accurate long-range rifles and machine-guns. The French army lagged a little behind, with the ‘horizon-blue’ blue-grey uniform (so-called as it was thought to prevent soldiers from standing out against the skyline) approved on 10th July 1914, and making the French dangerously conspicuous from day one in their blue and red uniforms.

From uniforms to aircraftÂ

It’s likely that this culture influenced the choice of aircraft colour. Conversely, Britain had learnt the benefits of drab green, and particularly ‘khaki’, from its colonial fighting in mid-19th century Punjab. This unattractive style, went out of ‘fashion’, but returned due to it excellence as a camouflage. By 1902, both the British and American land forces had gone khaki, something echoed in many of their aircraft in World War I.

In World War I, Germany and France both had some grey military aircraft. Examples of the former include the LFG Roland C.II, and of the latter, the Nieuports. A light blue-grey Nieuport 11 was flown by the French ace Georges Guynemer, which he named Oiseau Bleu (Blue Bird) — and some Voisin IIIs were painted in the same colour. By mid-1916 a silver-grey aluminium dope became the standard for French Nieuports until it was phased out in favour of a more disruptive scheme. Some Austro-Hungarian aircraft, for example, were painted with grey-based ‘lozenge schemes’.

The most successful fighter pilot, the ‘Red Baron‘, painted his aircraft red. This not only aided visual identification among allies, a vital factor in a fast chaotic dogfight where fractions of a second matter, but also offered the psychological advantage of scaring enemy pilots aware of his reputation. It is interesting that the most effective ‘dogfighting’ pilot spurned camouflage. I asked the RAF Museum about this:

Considering the Red Baron had a red aeroplane, is there an argument that bright colours offer advantages over camouflage; is quick identification friend-or-foe sometimes more important than the advantages of camouflage?

“The Red Baron’s red aircraft and other highly decorated aircraft of the flying circus obviously made the aircraft easily identifiable, it could also be seen possibly as intimidatory to the opposition, however, Austro Hungarian ace Julius Arigi, abandoned his highly decorative aircraft as he found that it drew the attention of the enemy.”

‘Sand and spinach’

By World War II, Britain’s fighter aircraft had disruptive two-tone uppers of earth and green, with a white (or black and white, or sometimes sky blue) lower half. In 1941, the Luftwaffe switched tactics: more fighting was taking place at higher altitudes where British schemes were dangerously visible. The Air Fighting Development Unit at Duxford considered the problem and concluded that the scheme should be toned down. The dark browns should be replaced with ‘Open Grey’ and the underside should be ‘Sea Grey’. A trend had started. Clearly, grey would be of the greatest benefit to the aircraft that spent the highest percentage of their missions at higher altitudes. With this in mind I asked the RAF Museum, if (as Thomas Newdick of AFM) believed, the all-grey scheme was first applied to the Welkin high-altitude fighter. ‘Welkin’ is a noun for the sky or heaven).

What was the first application of all-over grey as camouflage, was it the Welkin?

“It would appear that the first all grey trial occurred in May 1941 when a PRU Mosquito at RAF Benson was painted with a Medium Sea Grey/ Olive Grey scheme. It proved very effective, but it was felt it would be difficult to introduce to existing aircraft as the workload of stripping, priming and applying the new scheme would be too much work.

The first grey scheme to be used operationally was in June 1943 when it was approved for use on high level fighters, this included Spitfires, Welkins and some prototype aircraft.”

How was grey decided upon?

“Grey was adopted for high altitude fighters on upper surfaces as when viewed from above the ground looked grey due to cloud or dust particles in the air below.”

What is the advantage of grey?

RAF and Luftwaffe aircraft markings in World War II moved away from dark colours towards paler, greyer tones. One exception, though, was the Luftwaffe’s move towards darker, more disruptive schemes than ‘ground camouflage’ as they began to lose the war.

A P-38 wearing ‘haze paint’.

Low-viz markings: a mystery solved

Six years ago we tried to explain the mystery of ‘low-visibility’ national markings on military aircraft. Essentially we couldn’t understand why markings, something supposed to be clearly visible, were increasingly low-key on modern military aircraft. The idea of camouflaged markings seemed oxymoronic to the point of madness, but finally we can answer the question, thanks to the RAF Museum:

Considering national insignia are intended to be seen, why are modern national markings painted in low observable colours? Is there a legal requirement to carry them?

“The reason for low-observable markings is to reduce the risk of compromising the aircraft camouflage paint scheme, aircraft rarely come into visual range nowadays and aircraft are most likely to be identified by IFF. Yes, it is a legal requirement under the Chicago Convention.”

Ah, so these markings are paying lip service to a law! So what was the Chicago Convention? It was a convention on International Civil Aviation, drafted in 1944 by 54 nations. The stated aim was to promote cooperation, friendliness and understanding around the world. The US government invited 55 states (some of whom were still occupied) to attend an International Civil Aviation Conference in Chicago. Travel for many of the attendees was very dangerous (the war was ongoing in many places), but all bar one managed to attend (we’re not sure which country failed to send a delegate – answer in the comments below if you know). By the end of 1944, 52 states had joined the convention, and by 2019 there were 193 members. Find out more about the Chicago Convention here.

Has the convention been broken? Well, various nations have operated unmarked state military or para-military reconnaissance and transport aircraft. The conflicting needs of camouflage and identifying markings have a parallel in the natural world – for example, in the balance between camouflage and breeding plumage in birds.

We can only carry if our readers donate. Seriously, please do consider this. If you’ve enjoyed an article donate here. Recommended donation amount £14. Keep this site going. Huge thank you if you have already done this. If you prefer Patreon you can find that here.Â

1976-1985: The beginning of the end

In 1976 the F-15 Eagle entered service. It would define the Air Superiority fighter for thirty years, and was originally delivered in ‘Air Superiority Blue’. By 1978, though, new ones were being delivered in a ghostly two-tone wraparound grey, and repainting of old ones was well underway. Former F-15 pilot Paul Woodford, in conversation with Hush-Kit, noted- “Blue was too easy to see (we called it “tally ho blueâ€), gray was harder to spot”

This action led to the blandest revolution since the introduction of the USB, the Great Graying. The Eagle was followed by the equally blandly painted F-16 and F/A-18. With these aircraft, especially the Hornet and Eagle, the two tones appeared so similar in some light conditions they may as well have been all grey. Which raises the question, what was the first fully grey one-tone grey fighter of the modern age? I thought the RAF Tornado ADV that entered service in 1985, was a strong candidate, but on closer inspection I noticed it had a pale belly. This was followed soon after by Spain’s all-grey Hornets. If you know of earlier examples, let me know in the comments section.

Soviet origins?

I’ve avoided the Soviet part of the story as it’s a story in its own right. The USSR had some grey fighters in World War Two and continued this with the early jets. Some MiG-17s were certainly allover grey, as were the aircraft of several export nations including Pakistan. The main motive for the grey paint on Soviet air defence fighters and interceptors may have been corrosion protection rather than concealment.

Mud-movers go grey

Western ground attack tactics crystallised in Desert Storm in 1991, favouring medium altitude attacks with precision-guided weapons to low-level operations. Two-tone disruptive schemes, intended to make it hard to see an aircraft from above against the background of ground terrain were now on the way out. This furthered the universality of grey, and by the mid-to-late 1990s, the RAF’s Tornado GRs had gone grey (albeit a darker shade than their air defence brethren). The same was not true of Russian Air Force aircraft, though, and many have retained disruptive tactical schemes.

Today, Western air powers remain in thrall to grey, though fortunately many African and Asian air forces have not abandoned colour.

Special thanks to the RAF Museum’s researchers.Â